According to a recent survey by Money Crashers, the majority of millennials believe they face more challenging financial obstacles than their parents did at their age.

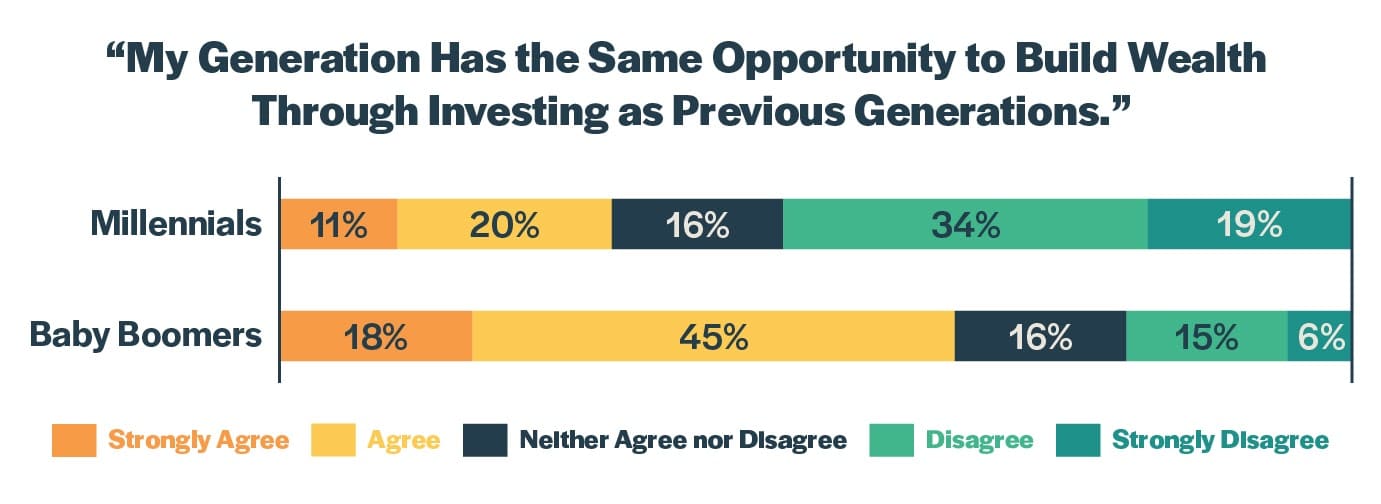

We asked Americans to rate their level of agreement with the following statement: “My generation has the same opportunity to build wealth through investing as previous generations.”

Millennials’ and baby boomers’ perspectives were noticeably different.

The majority of millennials (53%) disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement. By comparison, only 21% of baby boomers felt the same way. An overwhelming majority of baby boomers (63%) believe they have the same opportunity to grow their wealth as the generations that came before them.

What Do the Numbers Say?

Clearly, millennials think they’re at a disadvantage. But is that feeling accurate? Are they less financially well-off than their parents? Here’s what the numbers tell us.

1. Millennials Have Lower Income Levels

Millennials are more educated than their parents. According to Pew Research Center, 39% of millennials have a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to approximately 25% of baby boomers.

Yet despite being more educated, millennials are earning less. According to a report by New America, millennials earn 20% less than baby boomers did at their age. So it’s not surprising millennials have accumulated less wealth too. Pew Research Center found that the median net worth of households headed by millennials was $12,500 in 2016, compared to $20,700 for baby boomers in 1983 (adjusted in 2017 dollars).

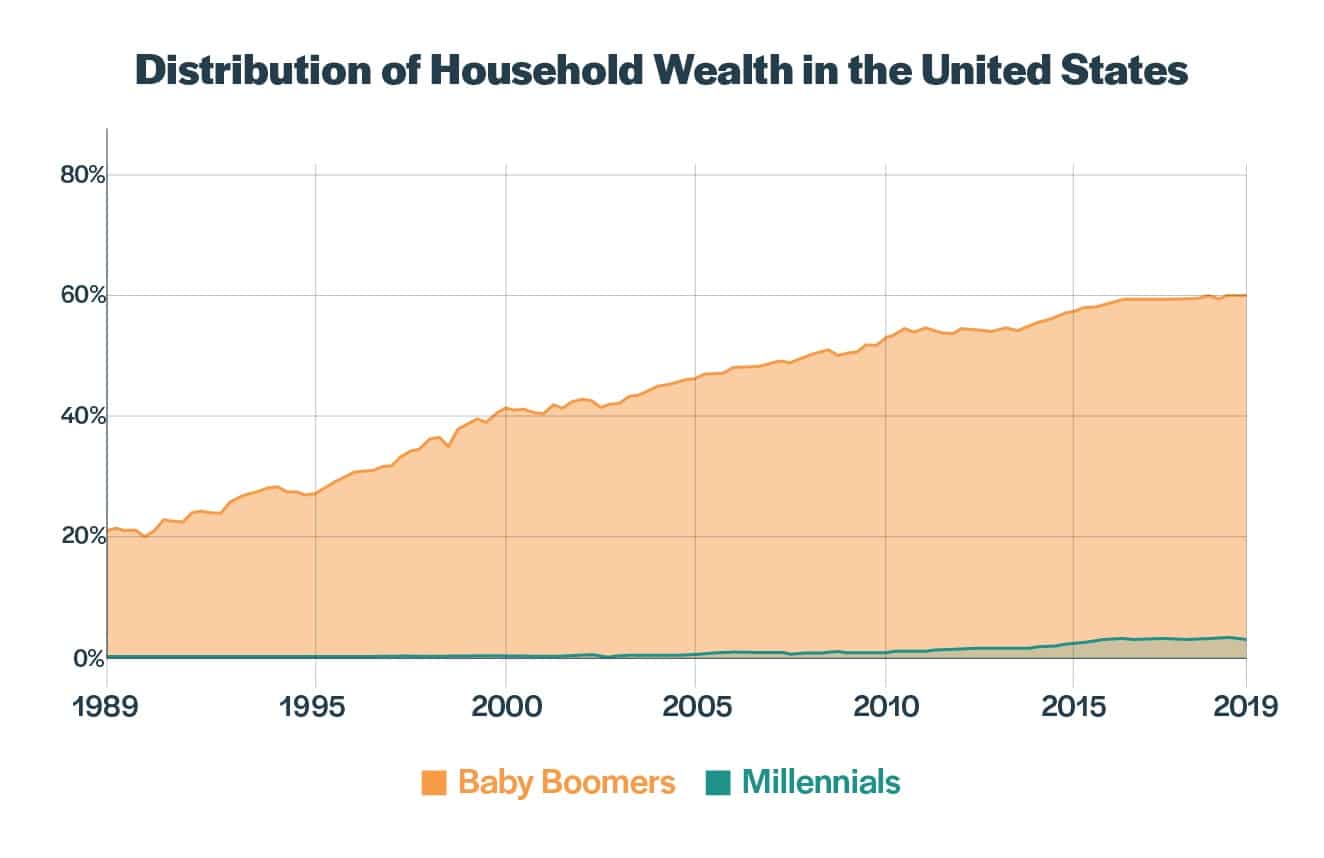

Millennials make up nearly one-quarter of the national population, yet they own only 3% of the country’s wealth, according to the Federal Reserve. When baby boomers were the same age, they owned 21% of the country’s assets.

2. Millennials Are Scarred From the Last Recession

Millennials came of age during the Great Recession, a time when the markets were crashing and unemployment rising. The downturn hit young workers particularly hard. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the national unemployment rate in October 2009 was 10.2%. But for young people between 20 and 24 years old, it was much higher at 15.6%. By comparison, it was only 7.9% for baby boomers between the ages of 45 to 54.

Melissa Gamarra, 25, lives in Salt Lake City. She runs her own consultancy specializing in online business management. Gamarra says the last recession had a big impact on how she views the financial markets:

“The recession really caused me to not trust the stock market. Especially as an adult learning how much of that crash was due to [the] recklessness of banks, stockbrokers, and illegal activity. I personally invest with Acorns, but I could never invest enough to generate a worthwhile return because my savings is not established enough.”

But experts warn that emotions shouldn’t affect how people approach investing. “The biggest factor limiting millennials from building wealth is an unwillingness to bear risk. The surest way to build wealth over long time horizons is to invest in a diversified portfolio of common stocks,” says Robert R. Johnson, professor of finance at Creighton University’s Heider College of Business. “The unwillingness to bear risk comes from a concern that we may soon see a market downturn.”

Although the stock market has recovered, research suggests there can be lasting consequences for people who graduate from school in a bad economy. For instance, they earn less money than those who graduate during more favorable economic conditions, even decades later. They start to work for lower-paying firms, which can have a lasting impact on the type and quality of jobs they hold throughout their careers.

Recessions are often depicted as short-term events. However, they have a long-term effect on people entering the labor force during an economic downturn.

3. Millennials Have Less Class Mobility

For baby boomers and the generations before them, a college degree was a ticket to the U.S. middle class. It didn’t matter what subject you studied. If you earned a four-year degree, you were likely to get ahead. In fact, a high school diploma was often enough to secure a job that allowed you to support a family. In 1970, only 26% of middle-class workers had any type of post-secondary education.

Today, things are different. A college education is merely the price of entry. Even with a bachelor’s degree, there’s no guarantee you’ll get a good job once you finish school.

Brice LaGrand is a millennial living in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He earned his undergraduate degree in 2013 from Eastern New Mexico University, one of the most affordable public colleges in the state. He then got an MBA, hoping it would open new doors. Currently, he’s working as a hotel manager, a role similar to the job he had in college.

“I grew up in a tourist town where every job was either in a restaurant or a hotel,” he says. “When I moved to Albuquerque in pursuit of a better job, I ended up at another hotel that I have been temporarily working at for several years.”

LaGrand has about $45,000 in student loan debt. He’s taking advantage of the gig economy to generate additional income. His side jobs have included dog walking, ghostwriting, cleaning houses, and even aerial dancing. But although he’s making progress toward paying off his loans, he recognizes he’s had to make significant sacrifices.

“It is difficult to find affordable, healthy food that can be fit around 14-hour days of work,” he says. “I haven’t gone on vacation in five years, and that also means I haven’t visited my family for the holidays. I have missed weddings, funerals, anniversaries, birthdays, and all sorts of other milestones because I have lacked both the time and money to do so.”

College tuition and fees have more than tripled since 1980, according to the U.S. Department of Education. As a result, millennials have to take on more debt to access middle-class jobs than previous generations did. But, like LaGrand, some are discovering that a four-year or postgraduate degree doesn’t guarantee upward mobility. The underpinnings of the cost and value of higher education have changed fundamentally.

4. Many Millennials Are Priced Out of Homeownership

For many Americans, owning a home is a cornerstone of the American dream. It’s a long-term investment for building wealth. You build up equity in your home by paying your mortgage each month. If you decide to sell your house in the future, you get to pocket your share of the equity.

It’s a strategy many baby boomers have utilized. They entered adulthood during a robust economy marked by large amounts of investment in construction and suburban real estate development. Homeownership was attainable for families with middle-class incomes.

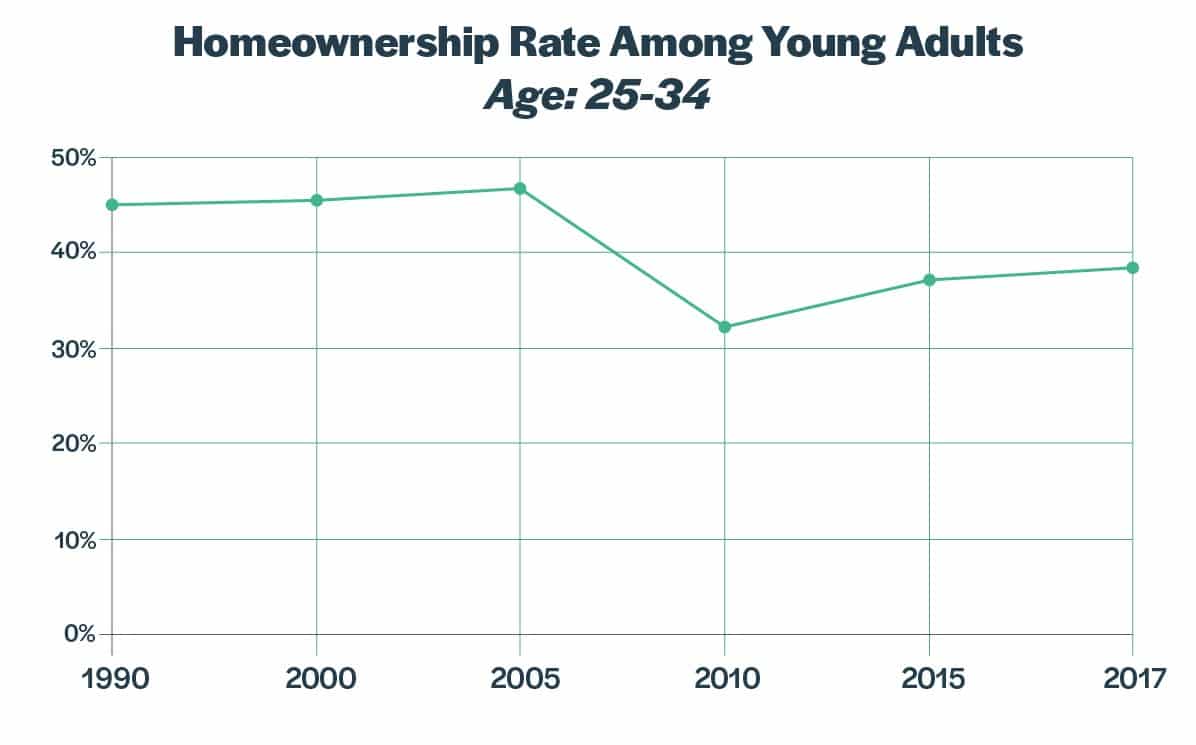

Millennials face a different housing market. Home prices have far outpaced inflation, while wages haven’t kept up with the cost of living. As a result, only 37% of millennials are homeowners. That’s 8% less than baby boomers at the same age. Saddled with debt, many millennials are forced to rent, live with roommates, or even move back in with their parents.

Millennials aren’t any less interested in homeownership. Research suggests their attitudes are not that different from earlier generations. According to one survey, 9 out of 10 millennials want to purchase a home.

Adam Jacobs believes the opportunity to own a home doesn’t align with the role his generation plays in the economy. After graduating from college in 2017, he struggled to land a job in the field he studied. Eventually, he was able to get his foot in the door as Director of Public Relations at Powerblanket, an industrial manufacturing firm. He lives in Rexburg, Idaho, with his wife and children. Even though Rexburg isn’t a large city, he’s found the local real estate market to be challenging for first-time homebuyers.

“Affording a home where I live always seems to be just out of reach,” he says. “I get a raise, and then home prices go up. I work harder and earn more, yet there is no ceiling to how high prices will go. It’s frustrating to see a home on the market that looks the same as it did two years ago, yet somehow it’s worth $20,000 more now.”

Like many of his peers, Jacobs is renting an apartment. He hasn’t transitioned to a starter home because there aren’t many affordable options in his area.

“Sure, developers are including more starter home neighborhoods in their portfolio, but those homes are overpriced and don’t fall within the realm of starter families,” he says. “Instead, the only homes affordable to young families are older homes with lots of repair work needed before moving in. It’s unfortunate that in order to achieve the dream of affording our own home, we have to deal with the generations that lived in that home before us.”

5. Millennials Are Responsible for Their Own Retirement

Retirement options have changed dramatically in recent decades. When baby boomers entered the workforce, many companies offered pension plans, which provide a monthly income to employees upon retirement. It was the employer’s responsibility to fund employees’ retirement through investments. Pensions represented a safety net that anchored workers to the same job.

The percentage of workers offered pension benefits has declined over the past 30 years. Only 13% of workers had access to a pension plan in 2018. Today, pensions are still relatively common in government jobs. However, in the private sector, the most common retirement plan is a 401(k), which is primarily funded by employees. That means workers must save for their own retirement and accept the risk if their investments decline in value. While this change has affected young and old workers, many baby boomers who remained with the same company throughout their career to qualify for pension benefits are in a strong position to be able to retire comfortably.

Tim Murray, an assistant professor of economics at Virginia Military Institute, notes that millennials’ savings are tied up in riskier assets.

“Having a pension plan gives a guaranteed income in retirement, whereas millennials are totally reliant on 401(k)s, 403(b)s, and IRAs for their retirement savings, which are invested in the market and therefore carry risk,” he says. “Knowing that if you work 30 years for a company and are guaranteed a certain percent of your income for the rest of your life changes your investment strategy compared to millennials who have to start saving in a risky asset for their entire career.”

6. Millennials Have Less Job Stability

The gig economy has transformed the nature of work. Online platforms like Uber, 99Designs, and Upwork allow people to provide on-demand services. Unlike traditional employment, gig work is contract-based. Workers are only paid for specific tasks and classified as independent contractors rather than full-time employees who receive benefits.

It’s difficult to measure the size of the gig economy because this type of work does not fit into the categories historically used to classify the workforce. According to a report by MBO Partners, 41 million Americans work as consultants, freelancers, contractors, solopreneurs, temporary, or on-call workers. A different study by Upwork and Freelancers Union found that 35% of Americans engaged in some type of freelance work in 2019.

For workers, the gig economy comes with pros and cons. It provides flexibility. Contractors can manage their own schedules and dabble in different types of work without the risk of losing all of their income.

Evan Waters, 30, graduated from Boston College with over $100,000 in student loans. While working for a tech startup in Silicon Valley, he provided digital marketing services on the side to supplement his income.

“Some years I made more from my part-time work than my full-time,” he says. “Three to four years of hard work and side hustles was all it took to pay off my debt. I was super fortunate to have an in-demand skill set.”

But not everyone has benefited from the gig economy. Many worry that gig jobs lack career growth and financial stability, placing the burden on workers to cover their own costs and benefits.

Jeremiah LaBrash, 34, is a software programmer in Los Angeles at a telecommunications startup. He believes gig work makes it harder to plan for the future due to a lack of job security:

“Many of my friends have had multiple career changes, as well as job changes, which is very different from the one-company, one-career path my parents have taken. On top of that, the gig economy seems to dominate where a lot of my millennial friends earn their money. They can’t invest as they’re not sure where their next job will be coming from. It seems that so much has changed from when my parents or grandparents worked and invested that their level of making and saving money is far out of reach for people of my generation.”

What Does the Future Hold for Millennials?

Macroeconomic forces have put young adults at a distinct disadvantage. They face a particularly bumpy road. Stagnating wages, student loan debt, declining social mobility, and the elusiveness of owning a home are making it more difficult for them to build wealth and make it into the middle class. Although the economy and the stock market have slowly recovered since the last recession, many millennials feel they missed the boat and are unsure how they will fare financially as they grow older.

Jordanne Wells, 34, lives in Cincinnati. She and her husband balance parenting two children with taking care of both their aging parents.

“Our conversations about the future go beyond just college planning and retirement,” she says. “We have to also consider savings for long-term care or an in-home care provider or the possibility that I will have to drop out of the workforce earlier than expected.”

While caregiving is not unique to millennials, it’s particularly challenging for those who are not on firm financial footing. Wells started her own blog, Wise Money Women, to address some of the financial hurdles she saw her peers experiencing. “I’ve found that so many folks, especially millennial women, are in similar situations,” she says.

Meanwhile, the United States government is $22 trillion in debt. And that debt has to be repaid somehow. As more baby boomers retire, the amount of tax revenue they contribute will be greatly diminished. They will become a financial burden for society because they’ll be taking money out of Medicare, Social Security, and other entitlement programs. The American electorate has been unwilling to concede any tax increases or reduction in entitlement benefits. They want to have their cake and eat it too. But someone has to foot the bill, and the burden will inevitably fall on the shoulders of millennials and subsequent generations of taxpayers.

That doesn’t mean the future is all bad for millennials, though. They have some advantages compared to earlier generations. There’s an abundance of free online material to learn about personal finance, including how to save and invest for the future. In addition, advances in technology have made it easier to open an investment account, while a proliferation of index funds allow individuals to earn market returns without significant transaction costs.

Murray believes millennials can overcome their financial challenges if they educate themselves and utilize the resources available to them.

“There are more financial instruments and tools available today than there were for previous [generations] at similar ages. While millennials have higher levels of debt and have more risk in their savings than previous generations did, that does not mean that the outlook for the future is bad. Starting to save as soon as possible and consulting with financial advisors and even taking finance courses is a great way to make sure that you are maximizing your savings potential. Don’t wait until your 40s or 50s to start consulting with advisors.”

Methodology

This is the second report of a multi-part series based on a survey of 1,017 adults conducted between July 7, 2019, and November 5, 2019, by Money Crashers. Responses were collected by sharing the survey on social media, email, and online forums and through Prolific’s panel services. For the analysis in this article, only responses from individuals between the ages of 23 and 38 (millennials) and 55 and 73 (baby boomers) who live in the United States (n=574) were considered.